Tings Chak is an artist, writer, and political activist whose multidisciplinary work stands at the vital intersection of art, life and social justice. Tings serves as the Art Director and researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, where her visual and written contributions are integral to shaping the institute’s powerful material on national liberation and socialist theory. Her voice extends through platforms like Wenhua Zongheng and People’s Dispatch, where her analyses on culture, politics, and global struggles offer crucial perspectives from the Global South and the oppressed.

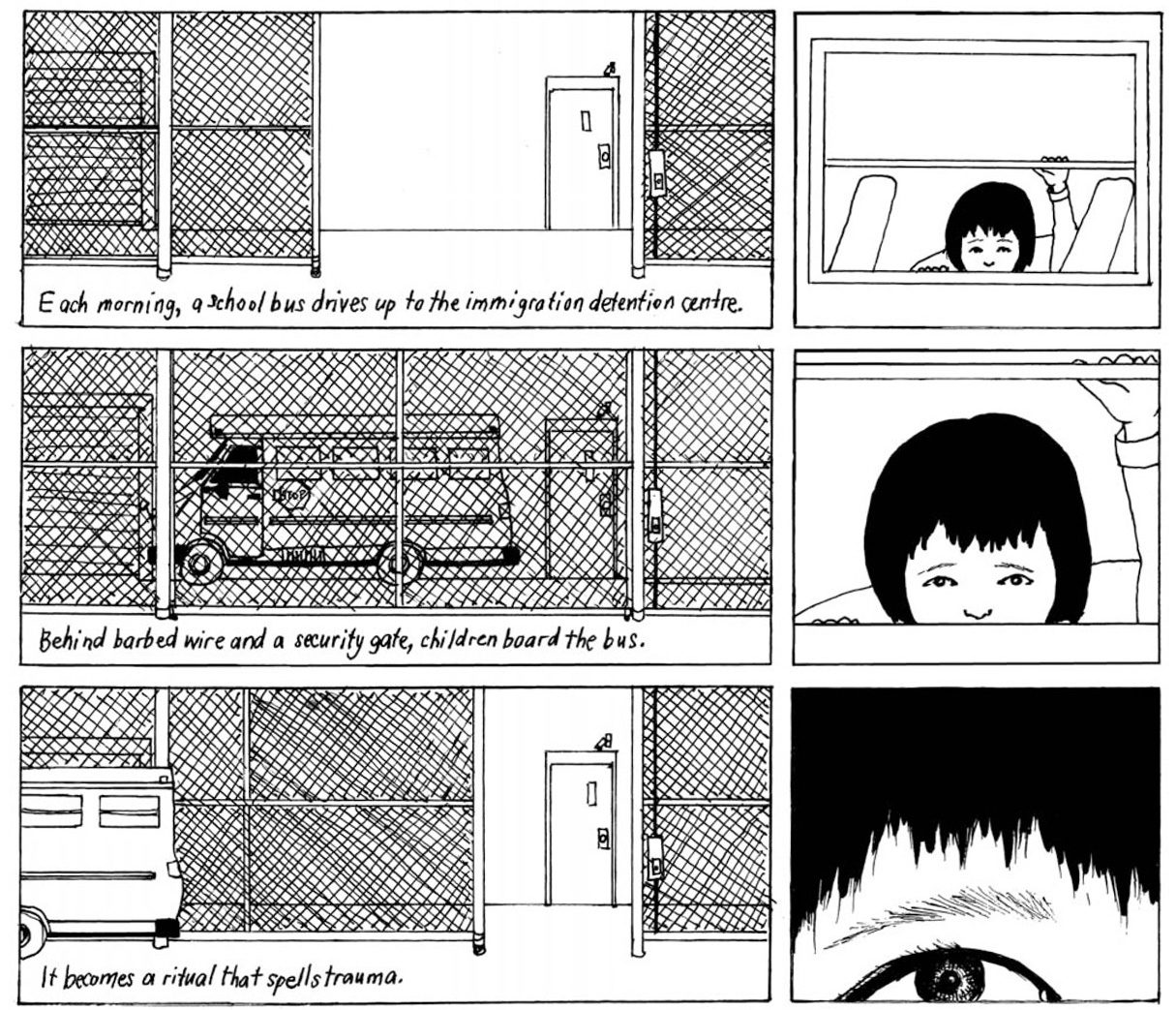

Chak’s artistic practice is deeply informed by her political commitments, often translating complex narratives of migration, resistance into compelling visual forms. Her acclaimed graphic novel and art project, Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention, exemplifies her method of using architectural drawing and narrative to critique state violence and make invisible systems of control starkly visible.

I tried to cover a broad field and different tasks to benefit all of her versatile background while talking to Tings:

***

When discussing a topic related to socialist, pro-socialist, or former socialist countries, you can really experience the power of imperialism’s propaganda and obfuscation. Despite historical “progress” and progress in technology, the veil over our vision does not lift, and the scale of the mystery does not lessen. Blindness, as described by Saramago, can cover the world.

That is why some of the questions we will ask you may contain questions you have already asked many times before, as well as stereotypes and illusions.

We will talk with you about the military/trade moves against China; the risk of these escalating further; the reactions of the CPC and the PRC; the current state of Chinese society and debates within socialism.

But first, I came across your work “Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention” a long time ago, which begins with “to the people who have resisted and continue to resist, borders everywhere.” It was an impressive work.

1- While preparing for the interview, I also read your other articles for People’s Dispatch, including “Art is the expression of our struggle.” You mention that art has an internationalist role. What is art’s internationalist duty?

I think that art from the national liberation and socialist traditions—which has been one of the focuses of my research—has always been about internationalism. I always turn to what Frantz Fanon wrote in his chapter on national culture in Wretched of the Earth: ‘It is at the heart of national consciousness that international consciousness establishes itself and thrives. And this dual emergence, in fact, is the unique focus of all culture’. In other words, just as there can be no national liberation struggle without internationalism, there is no culture of national liberation that is not at once bound up with internationalist culture. We see this internationalist duty resonate throughout historical struggles, and highlighted by experience of Cuba.

Our own institute’s name draws inspiration from the Tricontinental Conference hosted by Cuba in 1966, which celebrates its 60th anniversary in January. One of the outcomes of this conference was the creation of the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL), which published the Tricontinental magazine. In the pages of that publication that was sent in the thousands to revolutionaries across the Third World included beautiful, inspiring artworks, and a folded poster highlighting the liberation struggles of the day from Vietnam to Mozambique, from Nicaragua to Palestine—visual and material testaments to the spirit of solidarity of OSPAAAL and the Cuban Revolution. We document this in our dossier, The Art of the Revolution Will Be Internationalist, and I think the name, which is borrowed from a statement of the Cuban Congress on Education and Culture, says it all.

At the Tricontinental, we’ve been focusing on these traditions in several of our publications that I had the opportunity to write—and will hopefully come out in the next year as a book—including experiences in China, Cuba, Indonesia, South Africa, and Palestine. For us, recovering this historical traditions is not a nostalgic endeavor but it aims to look at past experiences—both the victories and defeats—to serve the present struggles and feed our future aspirations. “To use the past,” as Fanon said, “with the intention of opening the future, as an invitation to action and a basis for hope”.

2- You are one of the editors of Wenhua Zongheng. I believe it is a magazine that allows us to hear directly from Chinese intellectuals within China, amidst the fog created by the West. Is the magazine only oriented towards the outside world, or does it have a large readership within China as well? Can you tell about the magazine?

Wenhua Zongheng (文化纵横) is a Chinese journal published founded in 2008. It’s one of the most significant intellectual journals in contemporary China—bringing together a broad spectrum of left debates on China’s development path, theoretical questions within socialism, historical assessments, global affairs.

In 2023, what we at the Tricontinental started to do, in partnership with the journal, was create an international edition in English, Spanish, and Portuguese—two issues per year, curated for Global South audiences.

“Wenhua” (文化) means culture or civilization. “Zongheng” (纵横) literally means “verticals and horizontals” but alludes to the ancient school of diplomacy that helped unify China through statecraft and alliance-building. We keep the pinyin intentionally to bring a flavor of Chinese intellectual and historical traditions that may be difficult to translate.

The international edition tries to address a significant gap between Chinese thinkers and other Global South intellectuals. People from Latin America, Africa, Asia who may have genuine questions and curiosities about China often only have access to Western media or academic work produced within hostile frameworks. The conceptual landscape, the terms of debate, the key disagreements happening inside China—almost entirely unknown outside the country.

We are trying to build a bridge through this magazine, and our work more broadly, putting Chinese voices directly in dialogue with Global South readers, movement leaders, and intellectuals—something that is increasingly necessary with the escalating New Cold War that is being imposed onto China by the US and its allies.

3- A significant portion of Xi Jinping’s published theses on China’s governance covers ecological development. A couple of decades ago, China was the first country that comes to mind when talking about air pollution. Now, clearly, there has been a lot of progress. However, despite its magnificent nature, I cannot say that an ideal harmony has been achieved. In the program on Empire Watch, you talked about the recovery of Lake Erhai.

Could you share with our readers the Chinese government’s ecological program, the experience of recovering the lake, and your medium-term forecast?

A decade ago, you probably remember the reports on the environmental crisis in China, including the widely circulated images of the “airpocalypse” in Beijing, where I live now. I think there was a common sense understanding that China’s “economic miracle”—a term that I do not like because of its magical thinking—came at a cost, to both the Chinese working class and the environment, marked by heavy industrial growth, lax environmental laws, and the inevitable consequence of becoming the factory of the world. Fast forward a decade, after the government initiated the “war against pollution”, the situation has completely changed. To give you a sense, Beijing’s annual “good air quality days” went from 114 in 2013 to over 290 by 2024. PM2.5 concentrations dropped more than 42% between 2013 and 2021—a change that took the United States three decades, China achieved in less than one. Last year, China installed more solar and wind capacity than the rest of the world combined, and now has more renewable energy capacity than that of fossil fuel.

To understand this shift, we have to understand China’s own process of understanding the ecological problem. Already in the late 2000s, senior Chinese leaders were pointing to this problem, such as Pan Yue, then vice-minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, who said that China’s economic model was “unsustainable” and that “environmental pollution has severely constrained economic growth… social injustice leads to environmental injustice, which in turn exacerbates social injustice, creating a vicious cycle that brings social disharmony”. This similar critical outlook was raised by Xi Jinping as well, prior to becoming president, then in his 2022 report at the CPC’s National Congress.

In the last years, the “ecological civilization” (生态文明) has become the guiding vision, incorporated into the constitution 2018. Xi Jinping’s formulation—”lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” (绿水青山就是金山银山)—signals that environmental protection isn’t opposed to development but essential to it. This represents an ideological shift and a new direction for the country’s development, with the focus shifting from growth at all costs in order to develop the productive forces (Deng Xiaoping period) to “new quality productive forces” that take into serious conditions the ecological question.

The restoration of Lake Erhai in Yunnan shows how this works in practice, which I had a chance to visit for field research. I co-wrote an article with Xiong Jie that was published in our Wenhua Zongheng issue, China’s Ecological Transition. The lake—called the “Pearl of the Plateau”—had become severely polluted by the 1990s and 2000s, owing to the intensive garlic cultivation runoff, uncontrolled tourism development, and other factors in the post-reform period. In 2006, Erhai’s environmental governance was elevated to China’s national agenda as part of the State Council’s national ‘special project’ for water pollution control.

The intervention, led by the CPC, was systematic, including sending scientific teams to study the reality and identifying the key sources of pollution, such as the local garlic production. One of the lead scientists, Kong Hainan, himself a party member, not only led the study teams but also did the grassroots work, speaking with, educating, and convincing local peasant farmers to switch to less polluting crops as well as supporting the restoration of the wetlands around the lake, which meant relocating the many guesthouses and restaurants that had been set up there to a newly constructed community. All with the intention of convincing the local community that sometimes short-term individual or immediate sacrifices have to be made in order to preserve the long-term interests of everyone, namely the lake itself, which is lifeblood of the community and the local ecosystem.

In addition to dispatching scientific teams, “science and technology courtyards” were set up in partnership with the country’s top universities so that students would go to live, learn, and work alongside the local farmers and resolve their concrete problems. These are just some examples of how a national policy gets translated into local practice, the importance of science-based governance, and most importantly, the capacity of the CPC to mobilize across sectors of society—scientists, students, private enterprises, local governments, the civil sector, peasant farmers, etc.—under a common objective.

Since 2016, the lake’s water quality has been consistently received excellent ratings and has become a model project to demonstrate strong, comprehensive measures that are necessary to protect the environment and the collective commons. I hope you have a chance one day to visit Erhai Lake in the very beautiful region of Dali to see results of the restoration efforts, and the return of the local haicaihua flowers that have begun to bloom again.

4- You have also authored articles on the elimination of extreme poverty. Our readers will find some of your articles in online sources. I would like to ask you this: In economic and social development, it is known that there are contradictions between East/West and North/South, and that there is inequality in development, particularly in rural/urban China.

What is the strategy of Chinese society to combat economic inequality?

During the final push of the poverty alleviation campaign, I had a chance to visit villages in Guizhou Province, amongst the last communities to exit extreme poverty in the country. We wanted to learn about China’s Targeted Alleviation Program, which lifted the remaining 100 million or so Chinese people out of extreme poverty, beginning in 2013—basically those, especially in the Western and Central regions, who had not yet seen the economic benefits of the three decades of rapid growth of the reform period. I had a chance to talk with Party cadres, women, peasant farmers, youth, to learn about this experience and what we learned was fascinating.

The first impression was the scale of this campaign. In a country so large in population and territory, how do you even identify those who are impoverished, let alone identify how to create a plan to exit poverty? Here’s where the leadership and capacity of the CPC itself shows its strength. The Party sent 800,000 CPC members across the country, household to household to understand the conditions. Later, three million Party cadres were deployed to rural areas, stationed in 128,000 villages, working individual families so that each one of them could not only be lifted, but lift themselves out of extreme poverty.

Another important point was that, China did not rely on a cash-transfer system, understanding that poverty was rooted in multidimensional factors. So in addition to a poverty line—which was higher than the World Bank standards—, China added the two assurances of food and clothing, and three guarantees of access to medical care, safe housing with running water and electricity, education for children. We document this process in our study, Serve the People: The Eradication of Extreme Poverty in China.

This was not work localized in the poorer regions, but a huge direction of resources—financial, technical, governmental, human—from the more developed regions of the East to the West, in what was called the “East-West Cooperation”. So we saw not only the training of rural doctors and teachers, but the deployment of hundreds of thousands of them to the poverty-striken regions. Likewise, we saw the investments from state-owned and private enterprises from East to West. Cities would pair with poorer counties and send, for example, their vice-mayors to spend several years to share governance expertise and buildup local capacity. The women’s federations, universities, student groups, etc. were involved. This demonstrated

Often detractors of Deng Xiaoping’s reform policies point to his infamous phrase “let a few get rich” as condemning proof that China “restored capitalism”. Wittingly or unwittingly, the second part of his statement often gets omitted: “let those who get rich first bring others along”, holding sectors of society who became wealthier—a process enabled by the country’s economic planning in a particular historic period—responsible for ‘bring[ing] others along’ towards the goal of common prosperity. This reflects the poverty of information about China that exists outside of the country, an essential factor in the ideological battle over the concept of socialism.

Of course, eliminating extreme poverty is just a stepping stone towards socialist modernization, it’s not an end goal in itself. The period of reform did lift the economic floor for hundreds of millions of people—creating the largest “middle income” group in the world—but at the same time created high levels of inquality, which has begun to decrease over the past decades through such national campaigns as poverty alleviation.

The current framework is “common prosperity” (共同富裕). In practice this means: continuing rural development through the “rural revitalization” strategy; expanding social insurance (basic pension now covers over 1.07 billion people, basic medical insurance over 1.3 billion); reforming the hukou system that restricts rural-urban mobility (Zhejiang Province announced it will remove hukou restrictions except in Hangzhou); and—more cautiously—policies to “expand the middle and raise the bottom.”

What distinguishes China’s approach is that there exists market mechanisms but it is highly directed and oriented by the state, under the leadership of the CPC. And in some instances, the CPC will intervene in a coordinated way, such as the mass mobilization campaign against poverty, which also learns from the period of Mao Zedong, but under the very different conditions and context of today.

5- In the Asia-Pacific region, tensions are rising. Japan’s statements on Taiwan have been met with a strong reaction from the Chinese government. It cannot be said that tensions are on a cooling trend.

In Korea, the war between the Democratic People’s Republic and the US-backed South Korean government has been going on for decades.

In Southeast Asia, China is ASEAN’s largest trading partner in the South China Sea. However, the arming of the Philippines and Indonesia with NATO weaponry poses risks of militarization in the region.

The initiatives for an Asian NATO, which also includes Australia, are not exactly secret.

In the West, there are the Tibet and Xinjiang regions, which imperialism continuously provokes.

In particular, a trade war is being waged against China, pushed by the US. Among the current and ongoing elements of this war, we see sanctions, technology embargoes, pressure on Chinese companies, etc.

So, in summary, how do you assess imperialism’s policy of encircling the People’s Republic of China and China’s preparations?

To understand the pressures facing China today, we must situate them within what we at the Tricontinental have termed “hyper-imperialism“—a dangerous, decadent new stage of imperialism. Basically we see this period as being characterised by the relative economic and political decline of the US-led Global North bloc, and also increasingly its technological capacity. To compensate, US imperialism is escalating militarism. This bloc now accounts for over 74% of global military spending, the US alone spends 21 times more per capita on the military than China, which the West likes to condemn as a rising military power.

This hyper-imperialist context explains what we have been seeing from the genocide in Gaza to the provocations regarding Taiwan to the gunboat diplomacy and war crimes against Venezuela.

And the encirclment policy is real, not only marked by chain of US military bases surrounding China, which was increased, for example in the Philippines. The recent provocations by Japan must be understood in this contexto and through a historical lens. Remember that this year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the World Anti-Fascist War and the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. The parade we saw in Beijing on 3 September was an important symbol of China asserting its military capacity, not as an offensive force—China has not engaged in a war in nearly half a century—but as a modern military power very capable of defending itself and its people. Of course, the impacts of “World War II” as told in the dominant Western narrative erases the horrors of fascism in the region, and those who made the greatest sacrifices to defeat. We recently published a study that documents the West’s systematic erasure of the contributions of the Soviet Union and China to the defeat of fascism. The USSR suffered 27 million deaths; China lost at least 24 million, with total casualties reaching 35 million.

This historical erasure has political consequences. The same anti-communism that drove Western collusion with fascism before 1945 now informs the rehabilitation of Japanese militarism. When Japanese Prime Minister Takaichi invoked “survival-threatening situations” regarding Taiwan—the same legal framework Japan used historically to justify aggression in Asia—China’s response was severe. Beijing referenced the UN Charter’s “enemy state” clauses and held commemorations on September 3rd demonstrating China’s determination to defend itself. These were not displays of imperial ambition but a defensive posture informed by the living memory of invasion and occupation.

On the trade war, since the Xi-Trump meeting in South Korea, we have a seen a cooling of the tariff war, but we have to understand this to be a temporary concession. Ultimately, Trump’s economic bullying did more to hurt the US, from their corporations to the working people, more than China. According to the Tax Foundation, Trump’s tariffs amount to an average tax increase of $1,100-$1,400 per US household, while Goldman Sachs economists estimate that US consumers—or working people—absorbed 55% of tariff costs by the end of 2025. But we should not be fooled: despite the apparent “backing off,” the US National Security Strategy still identifies China as its principal strategic competitor. The temporary truce reflects the limits of tariff warfare—the US needs China’s rare earths, and China has demonstrated it can withstand pressure—not any fundamental change in US strategic orientation.

What the trade war has accelerated is a process already underway: South-South cooperation through trade and development of Global South multilateral platforms, such as BRICS, which expanded to eleven members in the last year, now encompasses roughly 45% of the world’s population and 35-40% of global GDP in purchasing power parity terms.

Our latest issue of Wenhua Zongheng on “Trump 2.0 and the Churning Global Order” examines this moment of transition. The return of Trump signals an upheaval in global politics, with the collapse of the neoliberal order giving way to new alignments, as the world reorganises and the “new mood” of the Global South finds its shape.

6- While China is being encircled from the external front, internally, reform and opening-up policies have increasingly strengthened capitalist production relationships in the country. A balance is being maintained with state-owned enterprises. It is often stated that capitalists exist but are unable to organize as a class. But in a world where capitalists are organized internationally, isn’t there a risk that international capital and imperialism will form ties with Chinese capitalists? What precautions are being taken against this?

This question gets at one of the central tensions in China’s socialist construction during the primary stage of socialism. In this stage—which Chinese theorists estimate will last until at least the middle of this century—private capital and market mechanisms coexist with a dominant state sector under the leadership of the Communist Party. There is no Marxist recipe book for this; it is a constant struggle to ensure, as Mao put it, that “politics is in command”—that the Party retains the capacity to direct development toward socialist goals rather than being captured by capital’s logic.

The reform period (1980-2012) saw rapid economic growth but also generated serious contradictions that Chinese leaders themselves identified: corruption, inequality, depoliticisation, and what Xi Jinping has called “money worship.” Capitalists accumulated enormous wealth and, in some cases, began to imagine that economic power should translate into political influence.

I can think of no better example than the Jack Ma episode to illustrate how the Party disciplines such tendencies, asserts that “politics is in command”. In October 2020, just before his Ant Group planned the $37 billion IPO—which would have been the largest in history—Ma publicly criticised Chinese financial regulators, comparing state banks to “pawnshops”. Within days before the IPO was about to be launched, the government stepped in. Ant Group was restructured. Ma himself essentially disappeared from public view for months. The message was clear: no capitalist, however wealthy, is above the Party, and economic power does not translate into political influence.

This was part of a broader campaign against the “disorderly expansion of capital.” The private tutoring industry—which had become a multi-billion dollar sector exacerbating educational inequality—was essentially eliminated. Anti-monopoly actions targeted major tech platforms. The slogan “housing is for living in, not for speculation” drove regulatory changes in the property sector. Meanwhile, Party cells in private enterprises have been strengthened—by 2023, over 1.6 million Party cells operated in private companies, with penetration rates above 90% across sectors. Since 2018, establishing a Party cell is mandatory for domestic stock market listing.

The results are visible, though not only owing to these measures, but the number of billionaires in China has dropped by roughly one-third in three years. This reflects deliberate policy choices to discipline capital and reduce extreme wealth concentration.

Simultaneously, the state sector has been strengthened. Strategic sectors—energy, telecommunications, banking, transportation, defence—remain under public control. The “new quality productive forces” strategy prioritises technological self-reliance in semiconductors and other critical industries. And the ideological dimension matters: the Party has revived “red” education initiatives—from schools to Party cells—to combat the influence of capitalist culture and reinforce commitment to socialist principles.

But I want to be honest about the limitations. China is not an island—even as it is marching forward in its socialist construction and modernization, it operates within an international capitalist system. Some Chinese capitalists share class interests with international bourgeoisie that may conflict with socialist development. The property sector, before recent crashes, concentrated enormous wealth. That is all to say, class struggle did not end when the CPC took power in 1949—it continues today in new forms.

Ensuring that the Party directs capital and the market economy, that socialist values prevail over “money worship”, that development serves the whole people rather than primarily enriches a minority remain living questions that are being addressed. The mechanisms China has developed to control capital are more sophisticated than any previous socialist experiment. It is something that we highlight in our Wenhua Zongheng issue, “Chinese Experiments in Socialist Modernization”.

7- What are the key points in the last 5-year development plan?

The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) marked a significant pivot in China’s development strategy. With extreme poverty officially eliminated in 2020—a historic achievement involving 98.99 million people lifted above the poverty line, 3 million Party cadres deployed to rural areas, and 800,000 representatives stationed in 128,000 villages—the focus shifted to what the Party terms “high-quality development.” This means moving beyond GDP growth as the primary metric toward a more balanced assessment that includes technological self-reliance, environmental sustainability, and reduction of inequality.

The plan emphasised “dual circulation”—developing domestic markets while maintaining international engagement—as a response to the uncertainties of the global economy and the reality of US decoupling efforts. Key achievements during this period include exceeding pension coverage targets (now over 1.07 billion people covered), expanding 5G infrastructure to over 90% of administrative villages, and maintaining China’s leadership in renewable energy. GDP averaged 5.5% annual growth despite significant headwinds.

The 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-2030), adopted at the Fourth Plenum in October 2025, comes at what Chinese leadership calls a “window of opportunity” amid intensifying global competition. Several shifts in emphasis stand out. The building of a “modern industrial system” has moved to the top of the agenda, with technological innovation following directly after. This sequencing reflects a practical focus: turning laboratory breakthroughs into scalable, high-value production capacity. Frontier sectors—advanced manufacturing, semiconductors, AI, aerospace, hydrogen, quantum technology—receive priority attention.

Technological self-reliance has become existential given US technology restrictions. The plan targets “faster breakthroughs in core technologies in key fields.” Progress is visible: Huawei’s recent smartphone releases using domestically produced chips despite sanctions demonstrate that China can innovate around US restrictions, though significant gaps remain in advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Common prosperity now carries concrete targets. For the first time, the plan specifies “a notable increase in household consumption as a share of GDP”—signalling serious intent to shift growth toward ordinary people’s purchasing power rather than investment and exports alone. This requires structural changes in how the economy generates and distributes value.

Carbon commitments are now binding goals. China remains on track to peak emissions before 2030, with targets to increase non-fossil fuels to around 25% of primary energy consumption and expand wind and solar capacity to over 1,200 gigawatts. In 2024, China installed more solar and wind capacity than the rest of the world combined.

8- Let’s move on to the last question, referring back to the first one. I ask this in light of art’s internationalist role. What do you think will be the most important issues for the international working class and communist movement in the coming period?

The principal contradiction of our time is between US imperialism and the peoples of the Global South. This is not abstract theorising—it is a violent struggle begin wages across multiple continents.

In Gaza, we witness genocide in real time: over 40,000 Palestinians killed, entire neighbourhoods erased, hospitals and schools destroyed, two million people subjected to starvation and forced displacement. The US provides the weapons, the diplomatic cover at the UN, and the political justification. Western “human rights” discourse has been exposed as the selective instrument it always was. In the Taiwan Strait, US provocations continue—arms sales, congressional visits, military exercises. These are not disconnected. Mao Zedong once told Palestinian leaders: “Imperialism is afraid of China and of the Arabs. Israel and Taiwan are bases of imperialism in Asia. You are the gate of the great continent and we are the rear. They created Israel for you, and Taiwan for us. Their goal is the same.” The two gates of Asia—Palestine and Taiwan—remain flashpoints today.

In Latin America, the Trump administration has declared what amounts to a renewed Monroe Doctrine. On 10 December 2025, US forces seized the oil tanker Skipper off the coast of Venezuela, carrying over a million barrels of crude, and Trump declared to reporters that they’d “keep the oil”. The US has targeted boats, killing at least 95 Venezuelans, threatened a land invasion, and announced a naval blockade—these are acts of war against a sovereign nation. Trump’s National Security Strategy declares the Western Hemisphere as “highest priority” and promises “targeted deployments” and “the use of lethal force.” Countries seeking US assistance must demonstrate they are “winding down adversarial outside influence”—meaning cutting ties with China. Interestingly, on that same day that the US seized the tanker, China released its third Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean, outlining a vision of partnership “without attaching any political conditions.” The contrast is stark: a “American-led world” maintained through violence, or what China terms “a community with a shared future for mankind.”

China’s role in this historical juncture matters for the global balance of forces, and for the future of socialism. When discussing or studying China, I do want to highlight two things to keep in mind. First of all, “China” is not one thing—there is the Chinese state, the Communist Party of China (and the diversity within that), the Chinese people (and its 56 ethnicities), Chinese SOEs, Chinese private companies, etc. Sometimes, I think many of the assessments about China flattens this very diverse and complex reality to claim that “China” that does or doesn’t do this or that. Secondly, China is not a utopia nor a perfect socialist model, nor does it claim to be. The experiment in “socialism with Chinese characteristics” involves compromises, tensions, and contradictions that Marxists must analyze critically. But China also represents the most significant alternative to Western capitalist development currently existing, and its survival matters for the global balance of forces, the weakening of US-led imperialism, but also for the preservation of the possible future for socialism.